New study reveals ancient Doggerland started sinking 10,000 years ago

Scientists have uncovered new evidence showing how Doggerland – the vast prehistoric landscape that once connected Britain to mainland Europe – was gradually overwhelmed by rising seas at the end of the last Ice Age.

Carbon dating on new core samples taken from the North Sea suggests its demise began around 10,000 years ago with rising sea levels due to melting icecaps.

The study, published this week in the journal Humans, uses detailed geochemical analysis of sediment from a core sample from the southern North Sea to reconstruct the final environmental stages that led to Doggerland’s disappearance beneath the waves.

Dr Mohammed Bensharada, from the University of Bradford, who led the study on the core sample, said: “Tracing organic residues and inorganic compounds within cored sediment, linking them to their origins, and then reconstructing a whole environmental picture around them, felt like solving a puzzle. Cored sediment provided a continuous archive of events, moving from one environment to the other, providing information about the missing land and the sea rising.

“We all know that Doggerland lies beneath the North Sea, but still the question; how much do we actually know about this mysterious place? This paper demonstrates the power of science by combining the capability of analytical and geochemistry with archaeology, detailing the final stage of Doggerland appearance.”

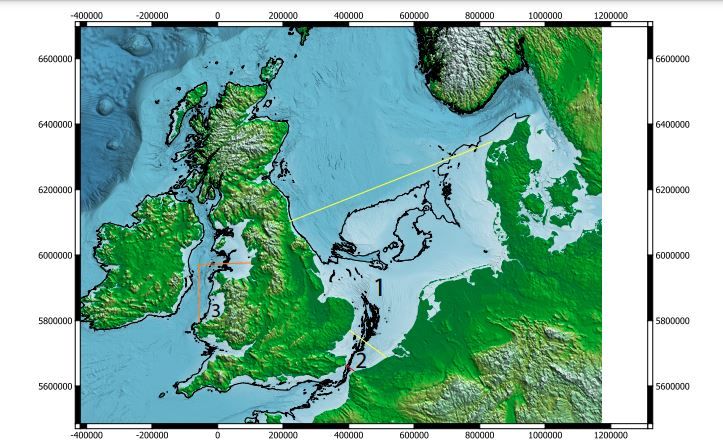

Graphic showing an outline of the now sunken landmass known as Doggerland. Picture credits: University of Bradford.

Final stages

Professor Gaffney, who leads the University of Bradford’s pioneering Sumberged Landscape Research Unit, said the findings provide one of the clearest environmental timelines yet for the final stages of Doggerland’s existence.

“Doggerland wasn’t lost in a single moment of drama. What we’re seeing here is a long, complex process of environmental change that would have unfolded over generations, repeatedly transforming how people lived in this landscape.

“By combining archaeology with high‑resolution geochemical science, we can now tell a much more detailed story about how Europe’s largest prehistoric landscape was gradually claimed by the sea.”

Core samples taken from under the North Sea, which revealed evidence of trees and plants, indicating the land was above sea level around 10,000 years ago. Picture credits: University of Bradford.

The science bit

Professor Gaffney said the team analysed a shallow sediment core recovered from the former landmass, applying a “multiple‑proxy” approach that combined thermal measurements, organic biomarkers, chemostratigraphy and radiocarbon dating.

Together, these techniques allowed the researchers to track subtle but critical shifts in vegetation, water conditions and sediment sources over time.

The results reveal a complex and gradual transformation, moving from freshwater and terrestrial environments to increasingly saline, marine conditions during the early Holocene.

Radiocarbon dating of organic material pinpoints a key transition to between 10,243 and 10,199 years ago, when rising sea levels began to dominate the landscape.

Core samples taken from under the North Sea, which revealed evidence of trees and plants, indicating the land was above sea level around 10,000 years ago. Picture credits: University of Bradford.

Chemical signatures

Crucially, the study shows that Doggerland was not lost in a single catastrophic event, but through a progressive process of inundation that would have repeatedly reshaped the lives and movements of the people who lived there.

Geochemical work was led by Dr Mohammed Bensharada and Dr Alex Finlay, supervised by professor Richard Telford and Dr Ben Stern, whose analysis focused on microscopic particles and organic residues preserved within the sediments.

By identifying chemical “signatures” linked to freshwater plants, terrestrial soils and marine inputs, the team was able to reconstruct changing environmental conditions with exceptional precision.

The research demonstrates how advanced laboratory techniques can unlock new archaeological insights from landscapes that are now completely submerged. It also strengthens the case for Doggerland as a dynamic, lived‑in environment that responded gradually to climate change rather than disappearing overnight.

Beyond Doggerland, the team say the approach could be applied to other submerged prehistoric landscapes worldwide, helping archaeologists better understand how early communities adapted to rising seas, an issue with growing relevance today.

Professor Vince Gaffney, who leads the University of Bradford’s Submerged Landscapes Research Centre. Picture credits: University of Bradford.